The spookiest thing about October has been the fact that I did a lot, without severe fallout. I undertook some big, tedious tasks, and some fun ones, too. Although I did suffer some episodes of post-exertional malaise, they were shorter and less severe than I’ve experienced in the past. Why? I think it’s due to a genuine improvement in my health, coupled with a little luck, and a drastic change in the way I plan and approach effort. Now, more than ever, I know my abilities, my limits, and how to plan around my needs. Today I’ll share my process.

Here are some highlights of the month:

- Family and Friends. I reunited with one of my closest friends for the first time since 2019. Our families spent a weekend together on the California coast. We had long talks about medicine, politics, love, and the future. We stood in the ocean.

- Medical Therapies. I met more doctors, both online and in-person, including a cardiologist, an allergist, and two neurologists.

- Star Sighting. I met Dr Michael Peluso, a prominent advocate and researcher for Long COVID. We talked about the ways physicians can approach Long COVID, and ways it might be categorized and treated in the future.

- Mentor Moment. I had coffee with my friend and mentor Dr Ludwig Lin on an absolutely perfect San Francisco day (talk about good luck!). His advocacy for physicians in marginalized groups, and his efforts to make healthcare an actually healthy profession for clinicians, gives me hope for the future of our field. Listen to the podcast he hosts for the California Society of Anesthesiologists to learn more about anesthesiology and direction it’s taking.Goodest Girl Aiofe, Dr Ludwig Lin, and Me

- Parenting Win. I answered my 10-year-old daughter’s questions about makeup, and took her to the local cosmetics shop. She bought her first lip gloss. Because my illness has impacted the ways I can be a parent, and has left me unable to engage with my children at times, this little experience was very meaningful. I’m going to carry this memory with me for a long time.

- Collaborations. I interviewed scientists, clinicians, and patients for the Long Covid, MD podcast. Experts spoke with me from their research offices at Johns Hopkins, Stanford, and UCSF; medical clinics in Oakland, California and rural Washington; and living rooms in New York City, Toronto, and the Bay Area.

As you can see, the last few weeks have been busy, and I’ve asked my body to carry me farther than it has in some time. How did I manage that?

Define Your Abilities and Limits

My first step is defining what I am able to do and what I should avoid. Then I respect those limits.

I organize activities into three categories: doable, difficult, and dangerous. I’ll use the example of traveling, which I did a lot this month. For Zeest Khan in October 2024, a large energy expenditure includes driving for 45 minutes to an hour. Driving for two hours, even as a passenger, is pushing it, and beyond that it’s no longer a large energy expenditure, it’s actually going past my limit. Thirty minutes is doable, an hour is difficult, three hours is dangerous. Because I live pretty far from a big city, driving three hours for a medical appointment is not uncommon. I’ll explain how I do that in a moment.

These trips strain me significantly, in a way I could not have imagined before falling ill. This is not typical health, and it’s certainly not my baseline. But I can tolerate a thirty minute drive now, and that is an improvement. In 2021, I could not safely drive that long. I had to be chauffeured for most trips, and to tolerate the trip I would often lie down and wear dark sunglasses with noise-cancelling headphones. I am in much better shape now, but as my endurance improves I am still clear on what I can and won’t do.

Avoid The Comparison Trap

To accurately assess my needs and abilities, I have to be honest with myself, which isn’t easy. I don’t enjoy acknowledging that my body is struggling, but I resist the urge to compare myself to unrealistic standards. I don’t measure myself against someone without a chronic illness, nor do I even compare myself to my pre-COVID self. The reason is simple: while I may see a very healthy body as a long-term goal, it doesn’t drive my day-to-day decisions. Those daily decisions impact my immediate health, and what I’m capable of in the near future. And actually, my own body is motivation enough. When I focus on my current abilities, I can see how they’ve improved and appreciate how far I’ve come.

In the most recent episode of the Long Covid, MD podcast, I spoke with Harry Leeming, who takes a similar approach. Harry is the CEO of Visible, a biotracking and wearable device company whose products are designed for people with Long COVID. In our conversation, Harry explains it’s more helpful to compare our own health metrics across time than it is to compare our numbers to someone else’s, or even to a theoretical standard. This approach has been a critical aspect of my Long COVID recovery, and certainly helped me accomplish everything I did this month.

Listen to our full conversation to learn more about the ways wearable devices and biometric data can help manage Long COVID.

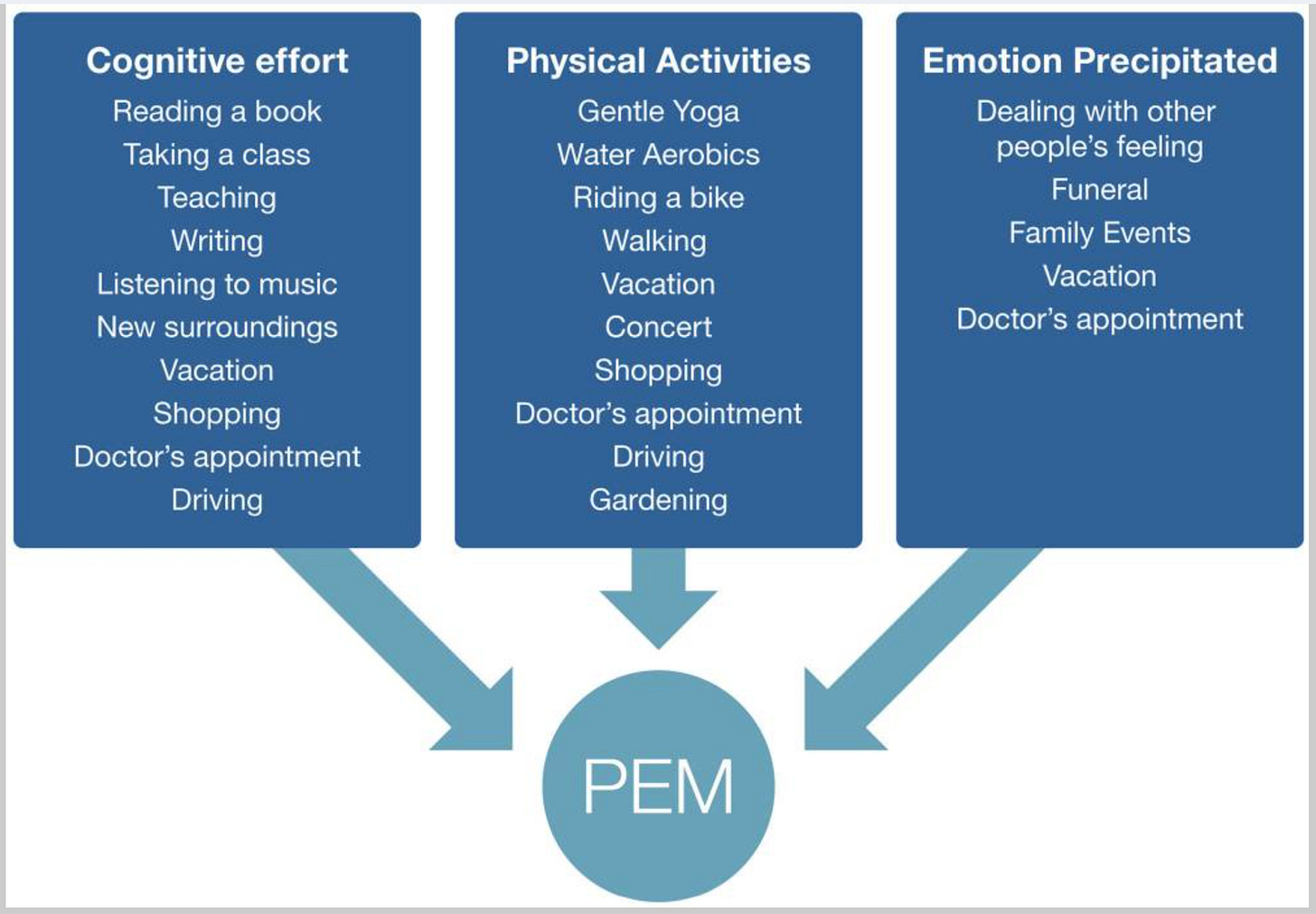

Push, Crash, Pace

Without a clear understanding of my abilities and limits, I risk falling into the “push-crash” cycle. In chronic illness, this cycle involves pushing ourselves when we feel well—or even when we don’t—and then dealing with the inevitable crashes that follow. Typically, a crash presents as post-exertional malaise. This pattern can become an unhealthy loop, making it nearly impossible to build on any prior progress. Each time we push too hard, we crash, leaving us in a perpetual deficit. Rather than building endurance, we end up just trying to catch up. An alternative approach is pacing: by consistently reducing activities, we can avoid crashing and focus on steady, manageable progress.

Easier said than done. For most, pacing requires a drastic change in lifestyle. It requires rearranging one’s life around new physical limits. For many, that rearranging is simply not feasible.

I don’t feel lucky to have had to step away from my medical career to recover from COVID, but I’m definitely grateful that I had the option to do so. Pacing my energy has been essential for my Long COVID recovery, and I could be even more strict with my routines. That being said, living every day in a repetitive, “Groundhog Day” style isn’t practical—or enjoyable. In the movie Groundhog Day, the main character experiences the same day over and over. Repeating the same day becomes frustrating, not comforting, and the hero tries to escape the monotony. His single goal is to live a day that is different and engaging.

The Emotional Toll of Pacing

This is part of the reason why, in addition to being financially burdensome, pacing can be emotionally draining. We’re forcing ourselves to NOT do. While I know plenty of people who don’t like change, and I do find comfort in some routines, experiencing Long COVID has taught me that I crave action, novelty, and challenge. These are probably the reasons I was drawn to heart surgery, and why it feels good to learn new skills to podcast and write.

We can’t underestimate the isolation that pacing introduces, either. We absolutely need community and friendships. Even small social interactions, like you’d normally have with strangers at the grocery store or bank, are meaningful. I don’t have much of that anymore, but my interactions with you and other podcast listeners have become surrogates. Through written messages and voicemail, we share news, updates, and sometimes we vent. Even when our messages are as short as a simple virtual ‘hello,’ the cumulative effect of this proxy water-cooler talk is genuinely meaningful and contributes to our psychological health.

Send me a voicemail from your phone or computer by visiting the link on the homepage. I might answer your question or comment on the podcast, or leave your email address for me to reply directly.

All this to say, I was thrilled to do more this month. And yes, pacing counts as doing—resting is an action too. Every day with Long COVID requires effort. But I think you know what I mean: I got to do more this month, and I’m grateful. If you’re able to do more than you used to, please celebrate that progress. If you’re still in that painful purgatory of severe symptoms, please know I sympathize and wish you a meaningful recovery soon. Over the past few years, I’ve spent countless hours isolated in a dark, quiet room. I felt like my own body was attacking me and I had no way to defend myself. I still spend part of every day in bed, but it’s nothing like those early days, months, and years. Still, I don’t take my current improvement for granted; I know that, like multiple sclerosis, this illness might follow a relapsing-remitting course.

Prioritize, Prepare, Pace

To do more this month without falling back into that abyss, I learned how to effectively pace my energy for big events. In order to meet my friends at the ocean, I did push myself at times. But most of time I existed in the “doable” or “difficult” category.

I prepare well before the event. In order to push on some days, I pace most days. This allows me to start a challenge at my optimized baseline. Before I make a push, I want to feel as good as I realistically can, so I do my best to get adequate sleep, hydration, nutrition in the lead up. I take my medications consistently and I also optimize my schedule. This means I clear out, cancel, and reschedule.

I take on one difficult task at a time, and leave myself time to recover, because it’s important to push as infrequently as possible. This means I have to prioritize my activities, saying ‘yes’ to a few things and ‘no’ to quite a few. I didn’t publish much for Long Covid, MD this month, because I simply did not have energy to podcast, write and undertake the other projects I listed. Doing too much would have put me in the danger zone.

Using Available Resources

It’s easier to remain in safe zones at home, where I can control most of my activity without needing too much help. For large energy-expenditure events, however, I need more help, and I find it. As I explained in an early episode of the podcast, I practiced medicine as a cardiothoracic anesthesiologist in the California Central Valley, which means I safely performed very high-risk procedures with limited resources. I learned how to utilize these resources judiciously. Judiciously means, use what you need, and only what you need. In heart surgery, as with Long COVID, sometimes a little will do. Other times, you need it all.

For a long trip, I need it all. I need someone else to drive. I need rest breaks, food, and comfortable lodging. I need someone else to plan and make decisions along the way. If it’s a vacation, I need a short daily itinerary, and lots of lounging. For my medical appointments in far-away big cities, I made the trip in stages, scheduled appointments on sequential days, and stayed overnight.

Let’s have a reality check here. What I’m saying is that, in order to stay safe, even for needed medical visits, I had help and I spent money. I don’t think it’s useful to sugar-coat that fact. Having Long COVID is expensive and we depend on others. Those of us with more resources are better positioned. I don’t spend money frivolously, that has never my tendency. But because I have Long COVID, I do spend a lot of money, almost entirely on medical treatments or accessing medical treatments. This month was no exception.

It helps that I know exactly what I need to get through a strenuous endeavor, the same way I know what I need to get a patient through open-heart surgery. In both cases, I have limited resources, but I do have some resources, and I use them for very specific reasons.

When everything is not available, it helps me to identify what is. What are your resources? What jar can you dip into to support your Long COVID journey, both physical and metaphorical? The answers will vary, because our social and economic realities vary. This also means our access varies, to both treatments and leisure activities.

Push Infrequently

As you can probably tell, I did not have a true push-crash episode this month, but these efforts were very challenging, and October’s schedule is not one I plan to repeat. Push-crash is dangerous and should be few and far between. If we extrapolate from the myalgic encephalomyelitis experience, unchecked exertion may cause our condition to permanently worsen. It’s why graded-exercise therapy is not advised. Please do not push your way through Long COVID. Your body does not respond to exertion the same way it used to, and you could be harming yourself.

Today, I discussed doable/difficult/dangerous and prepare/prioritize/pace. But it’s impossible to prepare for everything, and it’s impossible to pace our energy all the time. We are bound to face emergencies and unexpected events that push us beyond our limits. Allow yourself grace when you inevitably say yes when you ‘should have’ said no, or when you’re in the middle of a situations that cannot be avoided. In those cases, I do the thing that needs to be done as best I can, and when I’m able, I recenter my efforts on recovery. It’s remarkable how our bodies provide for us, how a surge of adrenaline can help us tend to an emergency. Being responsible to our bodies means we give it appropriate rest and resources afterward.

How was your October? How do you support yourself through challenges?

Hope you’re feeling well today…Zeest